Thomas Hieke/Tobias Nicklas, »Die Worte der Prophetie dieses Buches«. Offenbarung 22,6-21 als Schlussstein der christlichen Bibel Alten und Neuen Testaments gelesen, Biblisch-Theologische Studien 62, Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 2003.

Revelation 22:6–21 poses some riddles to the reader: Who is the speaker, and what is meant? This study concentrates on the process of critical reading. To read this text as the closing pericope of the Bible shows that important lines of meaning from the two-partite Christian Bible converge here. Apparently speaking in abbreviations, the text challenges its reader to import several passages from the Old Testament. This intertextual study shows that Rev 22:6–21 is not just the exaggerated end of an apocalyptic book, but the capstone of the Christian Bible. An excursus explains the authors’ decision for the Greek Bible as their basic text, i.e., the Septuagint and New Testament. Here one sees the efficiency of a reader-oriented and text-centered approach. The reflection on methodology and the concrete results of the analysis are closely related in the book. It comes with two indices (biblical references and topics).—T.H.

Dohmen, Christoph, Biblische Auslegung. Wie alte Texte neue Bedeutungen haben können, in: Hossfeld, Frank-Lothar/Schwienhorst-Schönberger, Ludger (Hg.), Das Manna fällt auch heute noch. Beiträge zur Geschichte und Theologie des Alten, Ersten Testaments. Festschrift für Erich Zenger, Herders Biblische Studien 44, Freiburg/Basel/Wien: Herder, 2004, 174-191.

D. explains the hermeneutics of a basic concept of interpretation adequate for the Bible and doing justice to exegesis in the discourse of scholarly theology. The object of the “Biblische Auslegung” is the Bible as literature and as an emerging composition of holy scripture during the canonical process, relevant and normative for a community of faith and practice. D. further reflects on the process of interpretation (“Auslegung”) in the context of current theories of reception. A key word is the intentio operis, a phrase coined by U. Eco. Hence, exegesis is not the search for the historical intention of the author as the one and only “correct” meaning, but a process that examines the spectrum of possible readings and the limits of interpretation. The framework of interpretation is defined (among other things) by the canon as the text world that a community of faith and practice receives as God’s word in human word.–T.H.

Steins, Georg, Amos 7-9 – das Geburtsprotokoll der alttestamentlichen Gerichtsprophetie?, in: Hossfeld, Frank-Lothar/Schwienhorst-Schönberger, Ludger (Hg.), Das Manna fällt auch heute noch. Beiträge zur Geschichte und Theologie des Alten, Ersten Testaments. Festschrift für Erich Zenger, Herders Biblische Studien 44, Freiburg/Basel/Wien: Herder, 2004, 585-608.

S. suggests a new reading of the visions in the Book of Amos. He starts with a presentation of the status quaestionis and numbers three assumptions that provide the basis for the current standard theory about the visions. Next, he shows five difficulties and problems with this “consensus.” S. presents his new analysis and interpretation of the visions in a discussion with J. Jeremias. His main point is to consider the context of the book for the interpretation of the visions. Then S. turns to the anchoring of the visions in tradition history and adds some considerations of their possible origin. S. concludes that the cycle of the visions do not build a bridge to the historical Amos, but the figure “Amos” rather serves as a focal point for a (“late/r”) discussion about theological basics. A chart demonstrates S.’s theory about the structure and the origin of the visions of Amos 7–9.–T.H.

Scheetz, Jordan M., Ancient Witnesses, Canonical Theories, and Canonical Intertextuality, in: Hieke, Thomas (Hg.), Formen des Kanons. Studien zu Ausprägungen des biblischen Kanons von der Antike bis zum 19. Jahrhundert (SBS 228), Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk, 2013, 12-39.

Through ancient testimony it is clear that the Torah (Law), Neviʾim (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings) are ancient divisions within authoritative Jewish collections. Although the content of the Torah is easy enough to identify from these witnesses, the particular groupings of the Prophets and Writings have proven to be more elusive. It is only with Baba Batra 14b that the contents and order of these two sections are actually given while this is clearly at odds with the earlier description given in Josephus’ Contra Apionem I.38–41. Standard critical theories of canonization heavily depended on fixed eras to bring the three divisions to their conclusion: 5th century BCE for the Law, 2nd century BCE for the Prophets, and 90 CE for the Writings. However, the facts that once were thought to support these theories have met their demise but yet their conclusions, namely what books must have been considered authoritative and approximately when, continue to live on. Newer theories focus not so much on dates but on composition and thematic placement. My own contention is that the authoritative books in this corpus (canon) were established in a time period before the Common Era, but that the shape of this corpus, with the exception of the Torah, was and continues to be in flux, primarily based on compositional and thematic issues, what I have labeled elsewhere canonical intertextuality.

Millard, Matthias, Die alten Septuaginta-Codizes und ihre Bedeutung für die Geschichte des biblischen Kanons, in: Hieke, Thomas (Hg.), Formen des Kanons. Studien zu Ausprägungen des biblischen Kanons von der Antike bis zum 19. Jahrhundert (SBS 228), Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk, 2013, 40-61.

The paper analyzes the role of the ancient uncial codices for the origin and history of the Christian Canon. The first part deals with the history of the canon. A brief overview sketches the development of the tripartite Hebrew canon and evaluates its Ancient witnesses. Then the paper turns to early Christian positions about the arrangement of the Biblical writings (e.g., Melito, Origen, Athanasius). The second part treats the arrangement of the writings in Codex Sinaiticus, Codex Vaticanus and Codex Alexandrinus. It elaborates what the three codices have in common and where they differ. Two basic types of arrangement can be identified: (1) Historical Books (including the Torah)—Prophets—Psalms and Wisdom versus (2) Historical Books (including the Torah)—Psalms and Wisdom—Prophets. The Codex Ephraemi Syri rescriptus (C) belongs to the first type that is also represented by Codex Sinaiticus and the Hebrew Bible. Only Codex Vaticanus represents the second type that Melito, Origen, Athanasius, and the later Septuagint manuscripts use. The paper speculates about possible reasons why arrangements of Christian Bibles used the Hebrew Bible canon type (1) for such a long time (up to the 5th century C.E.). The third part of the paper uses the Book of Daniel (and its various parts and Greek additions) as a test case for the influence of the canon arrangement for the interpretation of the text.

Leutzsch, Martin, Die Transformationen des lutherischen Kanons und der Lutherbibel, in: Hieke, Thomas (Hg.), Formen des Kanons. Studien zu Ausprägungen des biblischen Kanons von der Antike bis zum 19. Jahrhundert (SBS 228), Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk, 2013, 61-103.

Judaism and Islam have institutions in order to fix the language and wording of their respective canon. Christianity has no analogon to the Masoretes; hence the Christian canon shows a kind of flexibility and often is perceived only in the form of an established translation. Martin Luther transformed the Bible by his German translation in the following ways: the choice of the source text, the extent and structure of the canon, the accentuation and degradation of single elements, the fixation of interpretations and the integration of confessional polemics. By accepting the sequence of books of the Christian Old Testament (Codex Vaticanus) and discarding the Apocrypha, Luther created a new structure of the Christian canon. In his introductory paratexts, Luther provided a ranking of New Testament books according to their theological value. In glosses at the margins and through illustrations the Luther Bibles foster the Protestant understanding of Christianity.—Since the 16th century the Luther Bible itself was transformed by revisions in various ways. There exists a wide variety of new paratexts and sometimes even new translations were made during the centuries. Since 1850 the revisions were officially initiated and controlled by the Lutheran Churches. In the first half of the 20th century there is a tendency to exclude the Old Testament; after World War II several new projects of Bible translations (mostly ecumenical) were initiated.

Hübenthal, Sandra/ Handschuh, Christian, Der Trienter Kanon als kulturelles Gedächtnis, in: Hieke, Thomas (Hg.), Formen des Kanons. Studien zu Ausprägungen des biblischen Kanons von der Antike bis zum 19. Jahrhundert (SBS 228), Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk, 2013, 104-150.

The paper approaches the canon decision of the council of Trent (1546) by hermeneutics that are guided by memory and remembrance. An introductory part explains the terms and concepts of “communicative memory” and “cultural memory” as well as the relationship between remembrance and canon. The formation of the canon at Trent was a multitiered process of self-reassurance of a community of remembrance about her own foundations. The decision of the Council was the institutional framework in order to constitute and protect the community of remembrance “Catholic Christianity.” After a demonstration of the historical framework and Luther’s challenge of the traditional understanding of scripture the paper shows that the decision of the Council of Trent regarding the canon primarily had an ecclesiological dimension: The clarification about the canonical books of the Bible was neccessary for the description of the identity of the Roman-Catholic Church. The approach for fixing the canon was a historical one, i.e. a comparison of canon lists of earlier councils (especially the council of Florence, 1442). This act of remembrance was a recourse to the cultural memory of the Church. The paper provides a detailed comparison of both canon lists (Florence 1442 and Trent 1546). The list from 1546 defines the extent, but not the structure of the canon; whoever does not accept this extent is excluded from the Church. In the search for a single and common textual basis for the theological discussion within the Church, the council decided to use the Vulgate as this common ecclesiastic text. The reason for this choice was the long use of this well-proven text over centuries. However, the need for a standardized Vulgate text was fulfilled not before the publication of the Sixto-Clementina in 1592. The council did not exclude or proscribe the study of the texts in the original languages of Hebrew and Greek.—In their conclusion, the authors point out that the decision of the council of Trent 1546 made the canon an identity marker; the council defines the relationship between the canonical books and the community of interpretation (i.e., the Church). The definition of the extent of a canon of scripture does not nullify the necessity to interpret the texts within the community of faith and practice.

Smit, Peter-Ben, Ignaz von Döllinger und der Kanon. Von Polemik zum ökumenischen Konsens?, in: Hieke, Thomas (Hg.), Formen des Kanons. Studien zu Ausprägungen des biblischen Kanons von der Antike bis zum 19. Jahrhundert (SBS 228), Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk, 2013, 151-162.

This paper presents the understanding of the New Testament canon of the church historian and ecumenist Ignaz (von) Döllinger (1799–1890). Von Döllinger played a leading role in the (roman) catholic theology in Germany in the 19th century, both as a leading church historian, but also because of his leading role in the so-called “Old Catholic movement.” Both as a polemicist and—later—as an ecumenically oriented theologian, von Döllinger developed a pronounced view of the New Testament canon, the study of which contributes to the historical contextualisation of the contemporary discussion about this subject.

Steinberg, Julius, Kanonische „Lesarten“ des Hohenliedes, in: Hieke, Thomas (Hg.), Formen des Kanons. Studien zu Ausprägungen des biblischen Kanons von der Antike bis zum 19. Jahrhundert (SBS 228), Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk, 2013, 164-183.

The interpretation of the Song of Songs suffers from a diversity of conflicting approaches in scholarship. In this article, the problem is addressed from a canonical point of view. First it is argued that the secular and the mythological interpretation have to be judged as “a-canonical,” whereas allegorical/typo¬logical approaches as well as readings from the point of view of creation-theology can be considered to be canonical. To arrive at more precise conclusions, in a next step the position of the Song in the “contured intertextuality” of different forms of canon is examined. It is shown that despite the great variety in book orders in general, the Song of Songs is in most of the cases tightly connected to Prov and Ecc. This probably results from the Song’s ascription to Solomon, which is then discussed as being an intended canon-hermeneutical signal placing the Song into the realm of wisdom. Finally, several wisdom features of the Song are discussed, leading to the result that the canonical wisdom provides a very adequate and helpful context for understanding the message of the Song.

Wenzel, Heiko, Die unveränderte Abfolge Obadja – Jona im Zwölfprophetenbuch, in: Hieke, Thomas (Hg.), Formen des Kanons. Studien zu Ausprägungen des biblischen Kanons von der Antike bis zum 19. Jahrhundert (SBS 228), Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk, 2013, 184-208.

A comparison of the sequence of the Minor Prophets in the MT and LXX traditions leads to the surprising observation that the sequence Obadiah – Jonah is identical despite some differences for the first six books. This observation has not drawn significant scholarly attention or is considered a historical coincidence as is shown by a review of some models for the formation of the Book of the Twelve. A lack of entertaining alternative sequences might be the primary reason for this result. In light of these observations this article presents the thesis of Obadiah – Jonah as a two-prophet-book of unequal brothers. This thesis would require a revision of a widespread assumption. Rather than adding Obadiah and Jonah at different times and independently from each other, they would enter the Book of the Twelve together and simultaneously. This thesis has also methodological ramifications for the formation of the Book of the Twelve. A two-prophet-book of unequal brothers necessitates that the relationship between books is not only discussed on the basis of (obvious) commonalities.

Ballhorn, Egbert, Vom Sekretär des Jeremia zum schriftgelehrten Weisen. Die Figur des Baruch und die kanonische Einbindung des Buches, in: Hieke, Thomas (Hg.), Formen des Kanons. Studien zu Ausprägungen des biblischen Kanons von der Antike bis zum 19. Jahrhundert (SBS 228), Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk, 2013, 209-224.

The paper starts with a brief exposition of Jeremiah 36. The narrative solemnly demonstrates how oral prophecy step by step became the written word of God; God’s word in the prophet’s mouth becomes a scroll. Baruch, Jeremiah’s secretary, materializes God’s word. This constellation is used by the anonymous authors of the pseudepigraphical book of Baruch. Baruch’s profession and relationship to Jeremiah is not mentioned in the book but silently presupposed. The book wants to be read in the context of the book of Jeremiah, as it becomes clear already in the opening sequence: Baruch’s filiation connects him to the history of Israel; the beginning with καί indicates a continuation of something presupposed; the mentioning that Baruch wrote his book underscores the importance of writing. Baruch is a man of writing. His book is handed down always in close connection to the book of Jeremiah, and the authority of Baruch and his book derives from the authority of the great prophet Jeremiah. The canonical context in the Septuagint and Vulgate tradition thus provides clear guidelines for the interpretation of the book.—Presenting Baruch as a “scribe,” the book refers to the prominent role of scribes in antiquity and the Ancient Near East, as it is also depicted in Sir 38:24–39:11. Jeremiah’s secretary becomes a wise man, an author, a guarantor of tradition, a pious man praying for Israel.—Regarding the content of the book, almost nothing is “original;” it is a compilation of quotations from scripture. This way of writing happens intentionally; the author recons with readers that are acquainted with scripture and presupposes the existence of a “Bible” for his community. “God’s voice” is identified with God’s commandments written in the Torah. In the same way, wisdom finds its expression in the Torah. Hence, everything that Israel needs for a successful life is present, written down in Scripture. The book of Baruch presupposes already the closing of Israel’s collection of normative writings and constantly points to this unity of Scripture.

Hieke, Thomas, Jedem Ende wohnt ein Zauber inne … Schlussverse jüdischer und christlicher Kanonausprägungen, in: Hieke, Thomas (Hg.), Formen des Kanons. Studien zu Ausprägungen des biblischen Kanons von der Antike bis zum 19. Jahrhundert (SBS 228), Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk, 2013, 225-252.

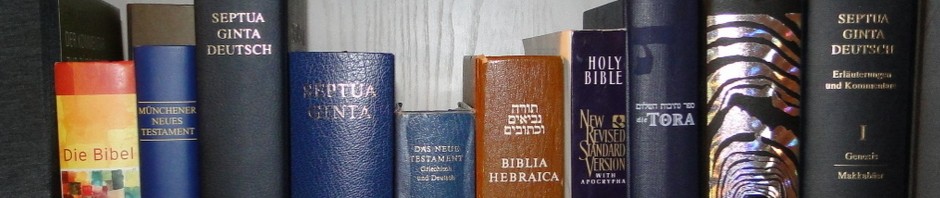

The term “canon” stands for the concept of a corpus of scripture providing identity and moral standards for a community of faith and practice. During the development in history different forms emerged: These manifestations of canon (also called “bibles”) differ in content and arrangement of their writings. This historical fact does not call a canonical-intertextual (or “Biblical”) interpretation in question but rather demands such an approach. The different arrangements of books in the respective Bibles (or manifestations of canon) create different contexts that have an important impact on the interpretation or hermeneutic perspective of the “whole.” The paper analyzes selected arrangements focusing on the joints or seams between the different parts of the canon manifestation, especially the transition from Old to New Testament: Depending on which books come to stand next to each other, the parts appear in a different light.